The visualization of details of an individual including Skype contact details, email, location information, and location within the hierarchy of an organization. Within Office 365, PersonaCards often appear when a user hovers, taps, or clicks on a Persona. This is a list of all Personas appearing in Persona 5.For the list of Personas in Persona 5 Royal, see List of Persona 5 Royal Personas. ↓ - denotes a Persona which has to be bought as downloadable content (DLC). DLC Personas do not contribute towards the completion rate of Persona compendium. Each DLC Persona package comes with both the original and 'Picaro' variant. 82 Followers, 1 Following, 0 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from @salvjiia. Customer Persona. The customer persona is a catchall term to describe your product’s main persona. It might be the user persona, for example, for a B2B product or be the buyer and user for a consumer-oriented product. For a business that sells products to other businesses, a customer persona could represent either the user or the buyer personas.

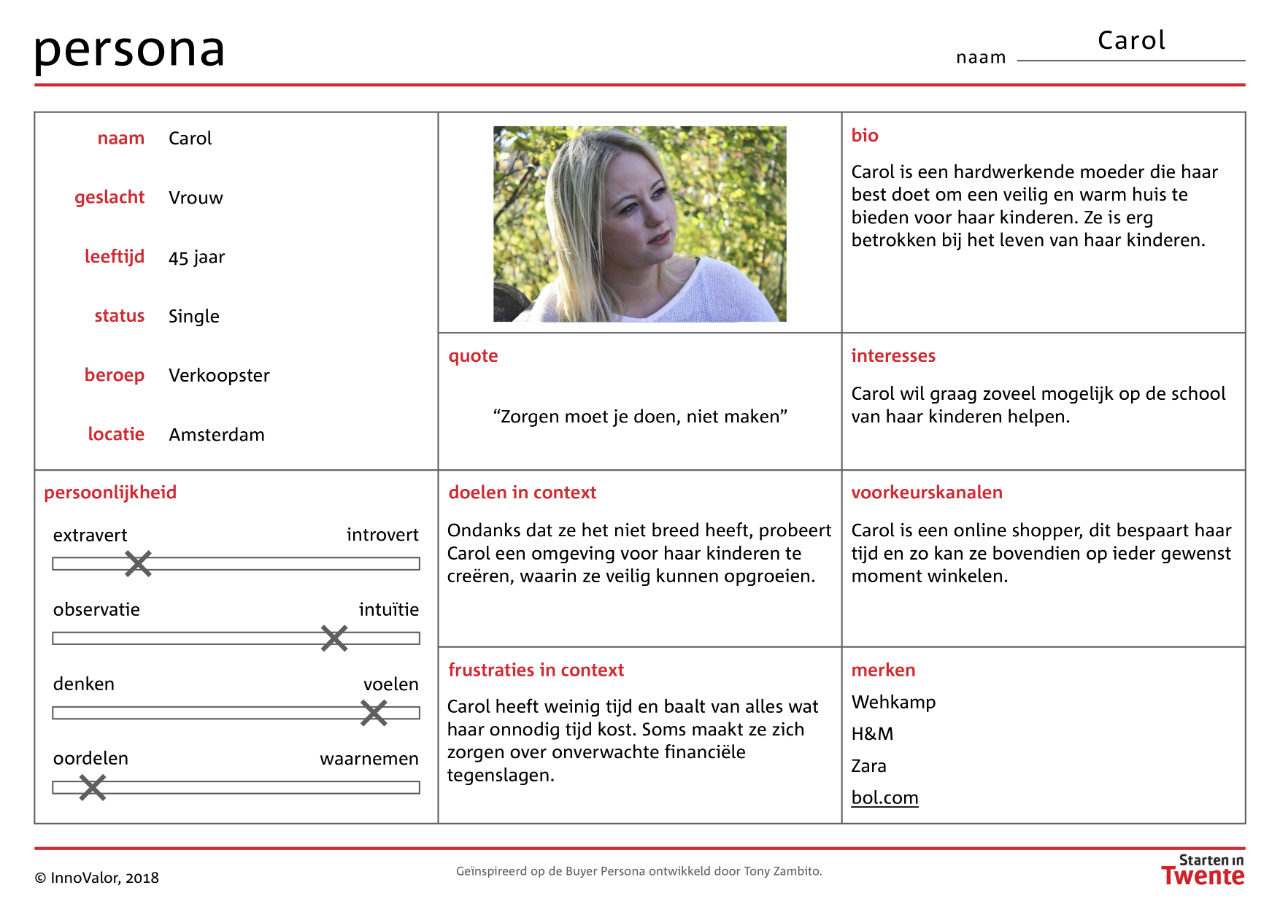

How well do you know your customers? If you’re like most of us, probably not as well as you should. One of the biggest mistakes marketers, product teams, and designers make is not developing a deep enough understanding of their customer’s needs and so making a lot of assumptions about how to solve for them. That’s why creating customer personas is so important.

What is a customer persona?

A customer persona (also known as a buyer persona) is a semi-fictional archetype that represents the key traits of a large segment of your audience, based on the data you’ve collected from user research and web analytics. It gives you insight into what your prospective customers are thinking and doing as they weigh potential options that address the problem they want to solve. Adele Revella, founder of Buyer Persona Institute, describes it like this:

Actionable buyer personas reveal insights about your buyers’ decisions—the specific attitudes, concerns and criteria that drive prospective customers to choose you, your competitor or the status quo.

Why are customer personas important?

Customer personas can provide tremendous value and insight to your organization. For example, they can help everyone on your team:

- Develop a deeper understanding of customer needs and how to solve for them

- Guide product development by creating features that help them achieve their desired outcomes

- Prioritize which projects, campaigns, and initiatives to invest time and resources in

- Create alignment across the organization and rally other teams around a customer-centric vision

And as a result, you’ll be better equipped to serve your customers and deliver a superior experience that keeps them coming back for more. But if you don’t nail down your customer personas, every aspect of your product development process, user experience, and marketing campaigns, will suffer. A lot has been written about how to create a customer persona. But wading through all the noise to find the best resources takes a long time. Here are the five best resources to help you create effective customer personas.

1. The Complete Beginner’s Guide to Marketing Personas

If you’ve never created a customer persona before, or if you need a quick refresher, we recommend starting with this guide from Buffer. You’ll get a high-level understanding of what customer personas are, why they’re important, and how to create them. While it doesn’t go into as much depth as some of the other resources below, it’s a great place to start learning.

Via Buffer

2. How To Create Customer Personas With Actual, Real Life Data

This guide from ConversionXL makes the case that, to be effective, personas need to be based on data-driven research, rather than opinions and assumptions. This section from the book sums it up well:

Patching together actionable information about your customers with gut feelings, good intentions and some duct tape is not a recipe for conversion success… The problem with many personas is that they are either based on irrelevant data, poorly sourced data, or no data at all.

Personalized Gifts

You’ll learn three ways to collect qualitative user feedback, and how to combine those insights with your web analytics data to get the complete picture of your customer’s behavior. You’ll learn that you need to use multiple sources of data to understand the motivations, attitudes, behaviors, and desired outcomes of your customers.

Via Mailchimp

3. How to Create Detailed Buyer Personas for Your Business

This resource from HubSpot gives you a step-by-step guide on how to conduct in-person customer interviews for your persona research. It goes into specific detail on how to set up your interviews, tips for recruiting interviewees, and exact questions you can ask during your interviews.

Via Hubspot

4. Personas: The Art and Science of Understanding the Person Behind the Visit

Although the introduction of this guide from Moz initially makes it sound like it’s only for marketers, it’s equally applicable to any UX designer or product team that wants to create a persona. This guide gets really specific about how to collect:

- Qualitative feedback - using customer interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic research

- Quantitative research - using your web analytics, market segmentation tools, multiple choice surveys, and other internal data

It also explains the difference between segments, cohorts, and personas, and gives specific use cases for how you can implement personas into your organization.

Via Moz

5. Quick and Dirty Guide to Creating Actionable Content Marketing Personas

This guide from the Content Marketing Institute shares essential steps to create and apply content marketing personas that get results you can put into action. Although it was originally written for content marketers, the underlying principles apply to designers, product managers, and other marketers too.

Via Content Marketing Institute

Bonus resources

If you’d like to learn more about how to create customer personas, see customer persona examples, and how to use them to enhance your entire customer journey, check out these resources:

Customer persona templates

Other bonus resources

Leveraging personas to create better experiences

Whether you’re a product manager, UX designer, or marketer, customer personas can help you develop a deeper understanding of:

- Your customer’s needs

- How to solve for them

- Which features, campaigns, and initiatives to prioritize

Just remember that your personas are only as good as the data-driven research that goes into them. They should be based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collected from multiple sources—not from the opinions and assumptions of your team.

Want to learn more?

If you’d like to learn how UserTesting can help you understand your customers through on-demand human insight, contact us here.

The persona, for Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, was the social face the individual presented to the world—'a kind of mask, designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and on the other to conceal the true nature of the individual'.[1]

Jung's persona[edit]

Identification[edit]

The development of a viable social persona is a vital part of adapting to, and preparing for, adult life in the external social world.[2] 'A strong ego relates to the outside world through a flexible persona; identifications with a specific persona (doctor, scholar, artist, etc.) inhibits psychological development.[3][4] Thus for Jung 'the danger is that [people] become identical with their personas—the professor with his textbook, the tenor with his voice.'[5] The result could be 'the shallow, brittle, conformist kind of personality which is 'all persona', with its excessive concern for 'what people think'[6]—an unreflecting state of mind 'in which people are utterly unconscious of any distinction between themselves and the world in which they live. They have little or no concept of themselves as beings distinct from what society expects of them'.[7] The stage was set thereby for what Jung termed enantiodromia—the emergence of the repressed individuality from beneath the persona later in life: 'the individual will either be completely smothered under an empty persona or an enantiodromia into the buried opposites will occur'.[8]

Disintegration[edit]

'The breakdown of the persona constitutes the typically Jungian moment both in therapy and in development'—the 'moment' when 'that excessive commitment to collective ideals masking deeper individuality—the persona—breaks down... disintegrates.'[9] Given Jung's view that 'the persona is a semblance... the dissolution of the persona is therefore absolutely necessary for individuation.'[10] Nevertheless, its disintegration may well lead initially to a state of chaos in the individual: 'one result of the dissolution of the persona is the release of fantasy... disorientation.'[11] As the individuation process gets under way, 'the situation has thrown off the conventional husk and developed into a stark encounter with reality, with no false veils or adornments of any kind.'[12]

Negative restoration[edit]

One possible reaction to the resulting experience of archetypal chaos was what Jung called 'the regressive restoration of the persona', whereby the protagonist 'laboriously tries to patch up his social reputation within the confines of a much more limited personality... pretending that he is as he was before the crucial experience.'[13] Similarly in treatment there can be 'the persona-restoring phase, which is an effort to maintain superficiality';[14] or even a longer phase designed not to promote individuation but to bring about what Jung caricatured as 'the negative restoration of the persona'—that is to say, a reversion to the status quo.[15]

Absence[edit]

The alternative is to endure living with the absence of the persona—and for Jung 'the man with no persona... is blind to the reality of the world, which for him has merely the value of an amusing or fantastic playground.'[16] Inevitably, the result of 'the streaming in of the unconscious into the conscious realm, simultaneously with the dissolution of the 'persona' and the reduction of the directive force of consciousness, is a state of disturbed psychic equilibrium.'[17] Those trapped at such a stage remain 'blind to the world, hopeless dreamers... spectral Cassandras dreaded for their tactlessness, eternally misunderstood.'[18]

Restoration[edit]

Recovery, the aim of individuation, 'is not only achieved by work on the inside figures but also, as conditio sine qua non, by a readaptation in outer life'[19]—including the recreation of a new and more viable persona. To 'develop a stronger persona... might feel inauthentic, like learning to 'play a role'... but if one cannot perform a social role then one will suffer'.[20] Thus one goal for individuation is for people to 'develop a more realistic, flexible persona that helps them navigate in society but does not collide with nor hide their true self'.[21] Eventually, 'in the best case, the persona is appropriate and tasteful, a true reflection of our inner individuality and our outward sense of self.'[22]

Later developments[edit]

The persona has become one of the most widely adopted aspects of Jungian terminology, passing into almost common parlance: 'a mask or shield which the person places between himself and the people around him, called by some psychiatrists the persona.'[23] For Eric Berne, 'the persona is formed during the years from six to twelve, when most children first go out on their own... to avoid unwanted entanglements or promote wanted ones.'[24] He was interested in 'the relationship between ego states and the Jungian persona', and considered that 'as an ad hoc attitude, persona is differentiated also from the more autonomous identity of Erikson.'[25] Perhaps more contentiously, in terms of life scripts, he distinguished 'the Archetypes (corresponding to the magic figures in a script) and the Persona (which is the style the script is played in)'.[26]

Post-Jungians would loosely call the persona 'the social archetype of the conformity archetype',[27] though Jung himself was always concerned to distinguish the persona as an external function from those images of the unconscious he called archetypes. Thus whereas Jung recommended conversing with archetypes as a therapeutic technique he himself had employed—'For decades I always turned to the anima when I felt my emotional behavior was disturbed, and I would speak with the anima about the images she communicated to me'[28]—he stressed that 'It would indeed be the height of absurdity if a man tried to have a conversation with his persona, which he recognized merely as a psychological means of relationship.'[29]

Jordan Peterson[edit]

University of Toronto psychology professor Jordan Peterson, well-known as an admirer of Jung’s work, uses Jungian terminology but reconfigures it into a model that divides the psychological world into the domains of nature and culture. The Great Father of culture is an archetypal force that shapes the potential of chaos into the actuality of order. In this framework, the persona would be the aspect of the personality that has been adapted to culture, more specifically to the social dominance hierarchy. People who refuse to submit to this social discipline or carry the responsibility inherent in having a role in the world remain as undifferentiated potential, known in more Jungian terms as peter pan syndrome, or the negative aspect of the puer aeternus. [30]

Though Jung doesn’t reference dominance hierarchies specifically, the above is broadly in accordance with his conception of the persona as defined in his Two Essays on Analytical Psychology:

Personal Creations

“We can see how a neglected persona works, and what one must do to remedy the evil. Such people can avoid disappointments and an infinity of sufferings, scenes, and social catastrophes only by learning to see how men behave in the world. They must learn to understand what society expects of them; they must realize that there are factors and persons in the world far above them; they must know that what they do has a meaning for others.” [31]

Personalization Mall

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^C. G. Jung, Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (London 1953) p. 190

- ^Jung, Two Essays, p. 197

- ^Mario Jacoby, The Analytic Encounter (Canad 1984) p. 118

- ^This is very similar to Sartre's waiter who becomes a sort of machine by denying his freedom and therefore limiting his potential growth

- ^C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (London 1983) p. 416

- ^Anthony Stevens, On Jung (London 1990) p. 43

- ^Terence Dawson, in P. Young-Eisendrath and T. Dawson ed., The Cambridge Companion to Jung (Cambridge 1977), page 267

- ^Barbara Hannah, Striving towards Wholeness (Boston 1988) p. 263

- ^Peter Homans, Jung in Context (London 1979), p. 100–2.

- ^C. G. Jung, Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (London 1953), p. 156 and page 284.

- ^Jung, Two Essays; page 277.

- ^C. G. Jung, 'Psychology of the Transference', Collected Works, volume 16. London 1954, page 238.

- ^Jung, Two Essays; pages 161–2 and p. 164.

- ^David Sedgwick, Introduction to Jungian Psychotherapy (London 2006) p. 153

- ^Stevens, Jung, page 179.

- ^Jung, Two Essays, p. 197

- ^Jacobi, Psychology, page 117

- ^Jung, Two Essays, page 197

- ^Hannah, p. 288

- ^Demaris S. Wehr, Jung and Feminism (London 1988), page 57.

- ^Susan Reynolds, Everything Enneagram Book (2007), p. 61.

- ^Roberte H. Hopcke, A Guided Tour of the collected Works of C. G. Jung (Boston 1989), pages 87–8.

- ^Eric Berne, Sex in Human Loving (Penguin 1973); page 98

- ^Berne, Sex; page 99

- ^Eric Berne, Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy (Guernsey 1966), p. 79.

- ^Eric Berne, What Do You Say After You Say Hello (Corgi 1975), page 56

- ^Anthony Stevens, Jung (Oxford 1994); page 47

- ^Jung, Memories p. 212

- ^Jung, Two Essays, p. 199.

- ^J.B. Peterson, 12 Rules for Life, p. 192.

- ^Jung, Two Essays, p. 197

Persona Game Series

Persona Games